On Kafka and Escaping into Literature

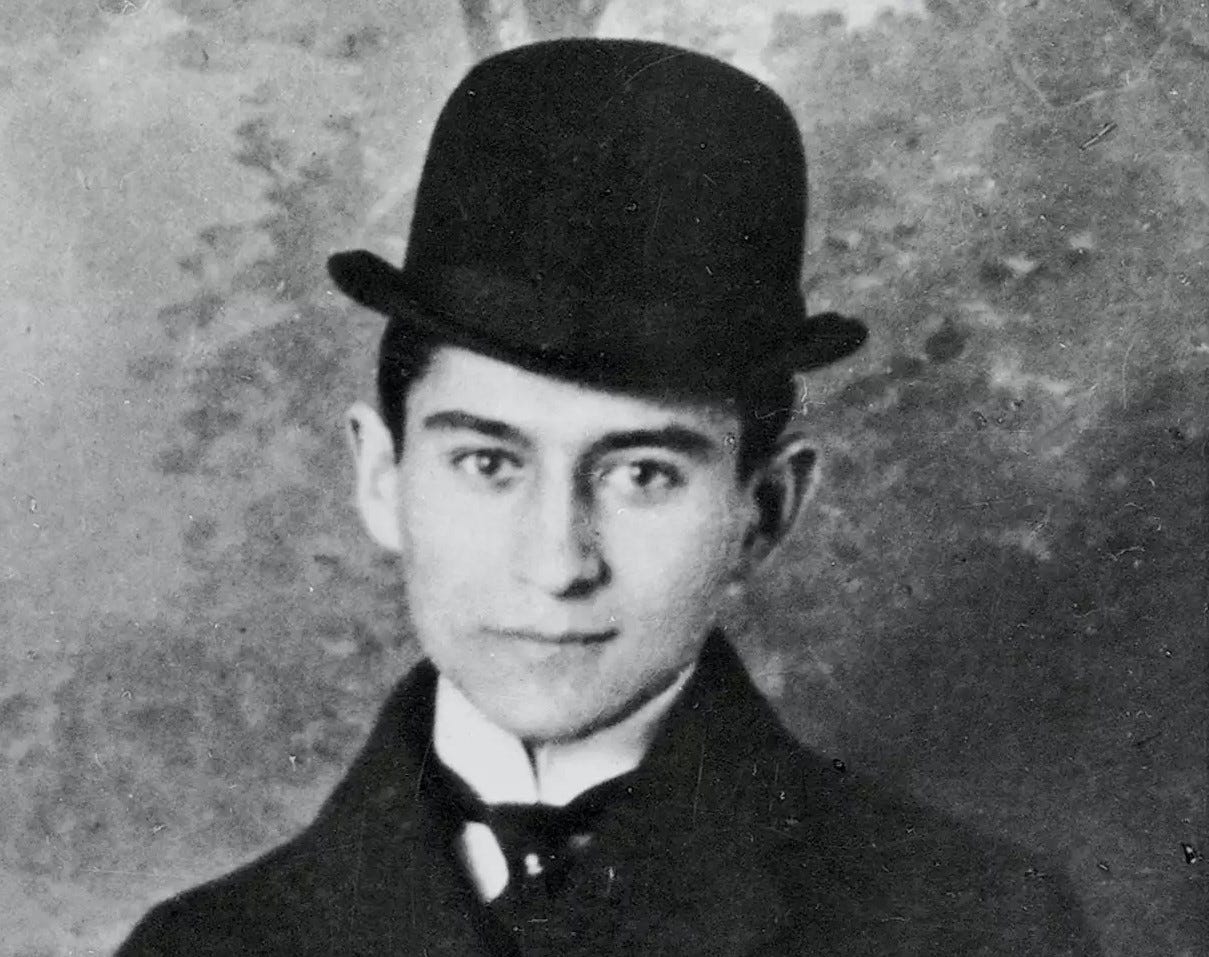

Franz Kafka had a strained relationship with his father Hermann. Hermann Kafka, a practically-minded salesman and retailer, was strong-willed, overbearing, and neither understood his son nor showed him the affection that the latter deeply desired. Anyone who has read Kafka's work closely knows that Franz struggled to escape Hermann's world and influence. One way in which he tried to break away from his father was through literature. At the same time, he recognized that escaping his father through the act of writing was an impossible, and perhaps even an absurd, task.

As Franz reflects in a poignant 45-page letter to his father, which he gave to his mother Julie to hand to her husband (which she never did):

"All my writing was about you; I only lamented there the things I couldn't lament on your breast."[1]

This assessment is clearly exaggerated, which does not make it any less heartfelt. Kafka's writing includes a number of overpowering father-figures, through which he apparently sought to exercise some form of control over his troubled and troubling relationship with Hermann. Think, for instance, of the father figures in The Judgment and The Transformation. Or in The Metamorphosis, where the horrified father famously drives Gregor back into his room after the latter's transformation. Nevertheless, as Kafka came to understand in and through his letter to his father, writing about his paternal grief and longing ultimately leaves him all the more dependent on his father—less in his life, perhaps, but all the more so in his writing. Ritchie Robertson, in his short work on Kafka, describes it as follows:

"The flight from life into literature must fail because literature has to be about life."[2]

I often think about this. Not just in light of Kafka and his work, but also in relation to myself and my own writing. It is worth asking: what exactly does or would the flight from life into literature mean? I think that there are at least two ways of understanding this idea. On the one hand, we can see the escape into literature as a flight into writing it, as in the example of Franz Kafka. We might flee from life into literary imaginings, formulating all sorts of alternative scenarios and possibilities, creating a different world.

However, rather than writing, we might also understand escaping into literature as referring to the act of reading. We might opt to consume literature, moving into a fictional world at the expense of the reality of the world around us. Like when I spent a summer reading The Brothers Karamazov in bed. In some sense, one could argue, every hour that is spent reading is an hour that is not spent living (whatever that means). If this assessment is to be understood in a normative or moralizing sense, I disagree, given that I value reading literature to the point that I think it constitutes living as much as any other activity that we might value (not everyone will, of course, agree here). Clearly, though, the act of reading literature necessarily entails not engaging in other activities—but this, in the end, goes for all activities that we choose to do at the expense of others that we might have done. In general, how we act at any given moment means that we are not acting in a different way at that time. Whether this constitutes escape will depend on our motives. Are we seeking comfort? Oblivion? If so, we might well be fleeing into literature just like we might escape into some other activity—watching a film, listening to music, or being seduced by the industry of mindless consumption, wallowing in the tepid entertainment provided by reels and YouTube videos to which we turn when we want to forget our day, ourselves, and simply tune in to something that drives our attention away from ourselves, especially when we are feeling anxious or sad.

"[I]t is, after all, not necessary to fly right into the middle of the sun, but it is necessary to crawl to a clean little spot on earth where the sun sometimes shines and one can warm oneself a little."[3]

It is tempting to consider writing to be a more active form of flight than reading. When we write, we are moved toward and building something that did not exist before. We are not simply being distracted; we are creating the distraction. Reading appears to be the more passive act—the material is already there; we just bring ourselves to it. There is some truth to this, although anyone who has read a novel by, say, James Joyce or Thomas Bernard, knows that more than passivity is required. Following a story, the relation of ideas, and so on, does not happen by itself. Our minds can never be purely passive, especially when we are reading literary texts.

"I should not like my writing to spare other people the trouble of thinking. But, if possible, to stimulate someone to thoughts of his own."[4]

All the same, one can probably get away with much more passivity while reading than while writing. Not all literary images and references have to be understood. Engaging with an author like Nabokov, for instance, means that one knows in advance that many possible references and associations will be missed. In writing, however, all aspects of (re)created life have to be considered, forged, brought out of oneself.

We might conclude that, through writing, one produces something tangible; while, through reading, one does not—at least not in the same way. Reading does not leave a physical mark on the world. It brings nothing new into it. Yet reading can, and often does, affect and change the reader. Literature can change one's understanding of the world, of specific persons and groups; it can inspire ideas and different ways of living. It can make one want to write. There might thus be a more indirect route through which reading literature can impact physical realities, to the extent that reading experiences may translate to and leave their mark on the concrete phenomena of the world. Works of literature can, after all, have far-reaching political consequences. Think of Ivan Turgenev's Sketches from a Hunter's Notebooks, which influenced public opinion and arguably led to Tsar Alexander II's decision to abolish serfdom in Russia in 1861.

In Kafka's unfinished story The Burrow (one of my absolute favorites), a mole-like creature is obsessed with creating an underground system of tunnels. His burrow is supposed to be entirely self-contained. It needs to be, for the creature seeks perfect protection from the world—absolute safety in its subterranean shelter. But the world is never perfectly safe and can intrude even when the world does nothing, merely through the possibility that, at any given moment, something might disturb us. A hateful creature could find its way into our lair. The mole-like creature in Kafka's story can neither forget nor accept this possibility. In response, it digs deeper and deeper into the earth, burrowing itself farther and farther into the ground. And the little creature can dig as much as it wants; into the deepest, darkest, most remote corners. As long as it remains aware that its path might possibly be traced by fearful enemies—that its being is still exposed to the world—it is all to no avail.

The burrowing creature, of course, represents us and our situation: we can do all that we want to try to avoid the world and its countless dangers, we can try to escape it and our situation to anywhere we like, but the world is always there and will come back to us for as long as we live. The same goes for literature and any attempt to escape into it. We can try to bury ourselves in writing, we can throw everything into creating a world where all is better, or understood better; but there is always a path that leads us right back to the world.

We cannot break out from the world any more than we can escape from ourselves. And why would we want to? The catalyst is usually our unhappy circumstances. Kafka's strained relationship with his father. Someone who is ill and wants to forget their illness. A dying person who wants to elude death. Literature might present a way out of a bad, or a partially bad life—but the paradox of addressing these oppressing circumstances through writing is that the only way to try to escape them is to confront them, however obliquely (and thus not to escape at all!).

If escape is not possible, transformation is. A reverse Metamorphosis: from the life of Ungeziefer (beetle? cockroach?) to a life that can only be imagined. We create literature and, with a bit of luck, it lasts beyond ourselves. Literature is, or can be, a way to confront our greatest fears and anxieties, to artistically embody our strongest hopes and desires, to give form and shape, color and depth to what lies within, before, and beyond us.

Of course, no matter what we create, we are left with our physical life, our histories, our material circumstances. Literature cannot replace these. But Varlam Shalamov may be right that "it's easier to bear a thing if you write it down. Once you've done that, you can forget."[5] Is processing and transmuting something dreadful—facing it, bearing it, making it yours, and moving on—not better than escaping it?

All literature is about life. We do not know about anything else. Kurt Vonnegut, for all his powers of imagination and celestial escapades, wrote books that are more about human beings and life on Earth than those of the staunchest realist. And the more Kafka writes about mole-like creatures, and bug-like critters, and dogs and mice and other creatures large and small, the more these come to seem like Kafka—and like us.

[1] Kafka, F. 2015. Letter to the Father. New York: Schocken Books.

[2] Robertson, R. 2004. Kafka: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[3] Kafka, Letter to the father.

[4] Wittgenstein, L. 2009. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe, P. M. S. Hacker, and J. Schulte. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.

[5] Shalamov, V. 1996. Kolyma Tales. London: Penguin Books.