The Last Day of a Condemned Man—Reflections on Capital Punishment through Hugo, Dostoevsky, Camus, and Boethius

Victor Hugo witnessed the workings of the guillotine at first hand. More than once, he found himself among the crowds of curious, expectant, agitated, hate-filled people awaiting the spectacle of a criminal being put to death. Repulsed by the joy that people seemed to take in these public executions, the idea of writing about it slowly began to form in his mind. After strolling along the Place de l'Hotel de Ville one day and encountering an executioner casually preparing the guillotine for its next victim, Hugo began working on the short novel that would come to be known as The Last Day of a Condemned Man. He finished it quickly and saw it published in 1829, albeit under a pseudonym. It would take three years for him to take ownership of the book; in 1832, he added a substantial preface explaining his aims and finally published the novel under his own name. Thus, he completed a work that Dostoevsky would later judge as "absolutely the most real and truthful of everything that Hugo wrote." And Dostoevsky was in a position to know—not merely by virtue of being a great writer and master of psychological realism himself, but through personal experience.

"It is a terrible thing even to condemn a terrible man."

— Vasily Grossman, Everything Flows

In the preface to The Last Day of a Condemned Man, Hugo summarizes the purpose behind his novel: to provide a generalized, yet accurate and compelling account of a man who has been condemned to death. In the preface, Hugo furthermore provides some arguments against the death penalty, and recounts—to the reader's as much as to his own horror—some stories about barbarically botched executions. The novel itself is meant to add dramatic force to Hugo's arguments, and it does. The reader is confronted with a detailed account of the thoughts and feelings of a (nameless) man who is awaiting execution by guillotine. The man reflects on external stimuli—the prison, the courtyard, the priest wandering to and fro—as well as on the changes, the fears and vain hopes, that he finds within himself.

We are left with an intimate and visceral picture of a man condemned to death. For what, we do not know for sure; it seems to be for murder. The reader is led to develop a certain amount of sympathy—not so much for the man himself (although his three-year-old daughter's failure to recognize him is poignant), as for the terrible condition in which he finds himself and in which, as Hugo would put it, no one ought to find himself. The main power of the novel lies in the final scene, when the inevitable occurs (the finality of the death penalty is precisely what makes it so terrible). The man in whose last moments of life we have partaken now finds himself among the masses screaming for his death.

"They say that it is nothing, that one does not suffer, that it is an easy end; that death in this way is very much simplified. Ah! then, what do they call this agony of six weeks, this summing up in one day? What then is the anguish of this irreparable day, which is passing so slowly and yet so fast? What is this ladder of tortures which terminates in the scaffold?"

—Victor Hugo, The Last Day of a Condemned Man

Hugo's concerns are echoed in Albert Camus's 1957 extended essay, Reflections on the Guillotine, in which the latter takes a strong stand against capital punishment. Camus's father had witnessed an execution by guillotine; and, while initially supporting it as a form of punishment, had changed his mind after having witnessed the deed (which, Camus recalls, left him in profound shock). While Hugo's novel is a fictional account of an execution, Camus provides a series of arguments and statistics in his essay against the effectiveness of capital punishment—in today's terms, questioning and undermining its deterrent effects.

Hugo and Camus may seem to be preaching to the choir for many contemporary readers. Compared to their respective times, few people today need to be convinced that the guillotine—or the death penalty more generally—ought to be avoided. This is true even if there are recurring appeals to reinstatement of the death penalty in places where it has long been abolished. Such calls for bringing back the death penalty tend to be tied to public perceptions of crime rates, the nature of particularly horrific crimes, and the sense that existing punishments are ineffective and/or insufficient.

Be that as it may, there is much to be said for the sheer conviction with which Hugo writes, his wholehearted commitment to the end of a savage practice, and for his support of the socially downtrodden. After all, the rich were not generally the ones who tended to receive the harshest punishments (nor do they now). In his preface, Hugo writes that "it has always been for those who are truly strong, truly great, to show concern for the poor and weak." In this way, Hugo shows himself as a great man; and likewise does Camus. At the time of writing, these perspectives were less established and much more pressing, given the prevailing practice of guillotining. Perhaps one can get closer to the public through fiction than through ethical-philosophical arguments: there is a reason why Hugo wrote a fictional Last Day, even though he did eventually supplement his dramatic account of waiting-for-death with reasoned arguments.

The question of how to deal with criminals is clearly alive today. It will always be so, for as long as human beings live together in groups. Group behavior needs to be regulated. Harms have to be avoided; survival is at stake. Given how unlikely it is that criminality will ever disappear from human societies, should we focus on punishing or on rehabilitating criminals? Although we no longer have the death penalty in places like the Netherlands (where I live), the questions are far from settled. Are we taking revenge for misdeeds when we imprison people, or are we removing malfunctioning and potentially dangerous members of society to reduce the chances of them causing harm to others? Is punishment meant to be—can it ever be—an example to others? We know that punishment is generally a limited deterrent; even in places with the death penalty, crime rates are not zero. Is there a better way?

Hugo offers his view of a better way—education—in his short story Claude Gueux, written in 1834 and often included together with Last Day. Here, Hugo writes: "This head, the man of the people's head, cultivate it, till it, water it, give it virtue, make use of it; then you will have no need to cut it off." Education, education—it takes time, effort, and patience. It is perhaps no wonder that people will sooner punish than try to rehabilitate; and not only because we as humans are inclined to experience all sorts of punitive intuitions and emotions. Here in the Netherlands, there have been serious lapses when it comes to rehabilitating criminals over the past years; freedoms have been given to those who, in retrospect, really ought not have been given them. Or so it certainly seems in these few but particularly vivid and tragic cases.

Camus's suggestion for an alternative to capital punishment in Reflections on the Guillotine is to improve living conditions. This, to me, seems at least as important as education, and probably even more so. Ensuring that people are able to live in decent conditions—that they are not fighting from birth for mere survival—should do much to reduce at least some forms of crime. Even then, of course, it is not as if there are no crimes among the affluent. The ideal of a crime-free society is a illusion; what we can do is try to figure out how best to reduce crime as much as possible, to prevent new crimes as well as recidivism.

"But secondly you say, 'society must exact vengeance, and society must punish.' Wrong on both counts. Vengeance comes from the individual and punishment from God."

— Victor Hugo, The Last Day of a Condemned Man

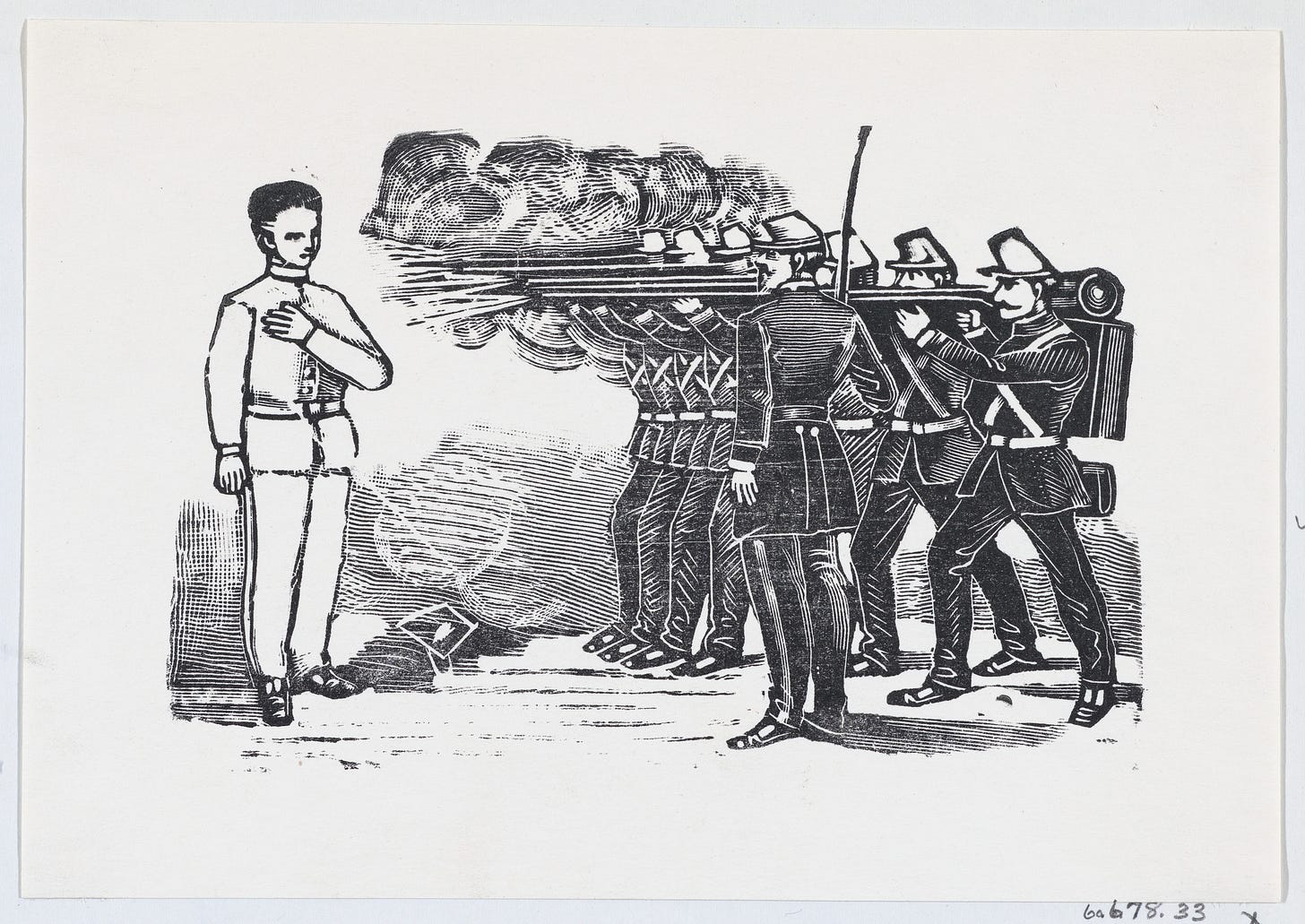

It is unsurprising that Dostoevsky was deeply affected by The Last Day of a Condemned Man, for he experienced a last day of his own. Condemned to death by firing squad for revolutionary activities with the Petrashevsky Circle, Dostoevsky was lined up among several others to be shot. For three minutes he knew—as far as he could know—that he would be killed. It was only at the very last moment that the execution was halted, that his life was spared. Some of the most moving and significant expressions of Dostoevsky’s mock execution experience can be found in The Idiot, where Prince Myshkin describes the story of an acquaintance (which is really that of the author). As Myshkin puts it: "Take a soldier, put him right in front of a cannon during a battle, and shoot at him, and he'll still keep hoping, but read the same soldier a sentence for certain, and he'll lose his mind or start weeping."

It is the certainty, the inexorable backing of the state/authorities, the irreversibility, the lack of any hope for a reprieve that makes capital punishment so dreadful. Dostoevsky turned to Christ in those last minutes, although the terrifying thing was that even He could do nothing there. "Who ever said human nature could bear it without going mad?" Hugo also turns to God (rather than us human being among ourselves) as the only rightful punisher. Yet the problem is that, in this life at least, we can turn to no other source for either our punishment or our salvation. It has to come from among us, from within us, somehow. Dostoevsky knew this better than Hugo. Those last minutes before the scaffold, the guillotine, the firing squad—Dostoevsky knew that nothing could save us there. And, accordingly, that no one should ever be put in that position.

Is there an alternative to God? The Roman philosopher Boethius embraced philosophy instead. While imprisoned and awaiting his execution in Pavia in the year 524—on charges of wanting to overthrow the Ostrogothic King Theodoric the Great—he wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, in which he engages with a lady who personifies Philosophy. In a fascinating mix of Greek philosophy, stoicism, early Christian thought, and Neoplatonism, Boethius philosophizes about human nature, virtue, justice, determinism in relation to free will, and on why evil often seems to triumph over good. This was his way of coming to terms with his impending death, of soaring beyond the inevitable moment; to locate his existence within a larger scheme (Divine providence, fate).

"The now that passes produces time, the now that remains produces eternity."

—Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy

In the end, Boethius left us with a beautiful, poetic, and meditative work—yet whether he actually came to terms with the irrevocability of the imposed end of his life, we do not know. I'm inclined to think that we cannot know: no matter what he might have told us.

In the face of execution, philosophy helped console Boethius, who in turn hoped that it might do the same for others. Writing about the experience, as Dostoevsky did, must also have been a relief—even if Dostoevsky himself never quite came to terms with what happened to him in front of the firing squad that day. Trying to speak about the moment when speech will leave us is one of the great paradoxes of human existence. The experience of speaking before it, certain that it will happen, must be indescribable, even if writers like Hugo and Dostoevsky have expressed it in such compelling ways. When given notice, we can at least prepare. But that's about it.

So interesting! will look up this work from Boethius, I've never heard of him before